New top story from Time: What the U.S. Can Learn About Health Care From This West Virginia County’s Successful Vaccine Rollout

“Hi, sweetie,” Dr. Sherri Young says to the 13-year-old rolling up her sleeve and giggling nervously, who also happens to be her daughter. “Are you ready?”

Young uncaps a syringe and pokes it into her daughter’s waiting arm. It’s May 14, only a few days after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration greenlighted the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for 12-to-15-year-olds, and Young is trying to set an example. As health officer and executive director of West Virginia’s Kanawha-Charleston Health Department (KCHD), she wants other families to bring their children to community vaccine clinics like this one, a drive-through set up in a church parking lot a few miles outside downtown Charleston.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Throughout the day, dozens of cars—ranging from a battle-tested garbage truck to a brand-new Mercedes sedan—roll in to the drive-through clinic. KCHD is relying on these smaller-scale pop-up clinics to bring in people who were unable or unwilling to visit Charleston’s 17 mass-vaccination events held throughout the winter and spring. In the early months of the vaccine rollout, those larger clinics attracted up to 5,000 people a day, but as time went on and most vaccine-eager people got their shots, Young and her staff had to get creative. “There are people who just can’t or won’t travel,” Young says. “Even getting out of the city two miles makes a difference.”

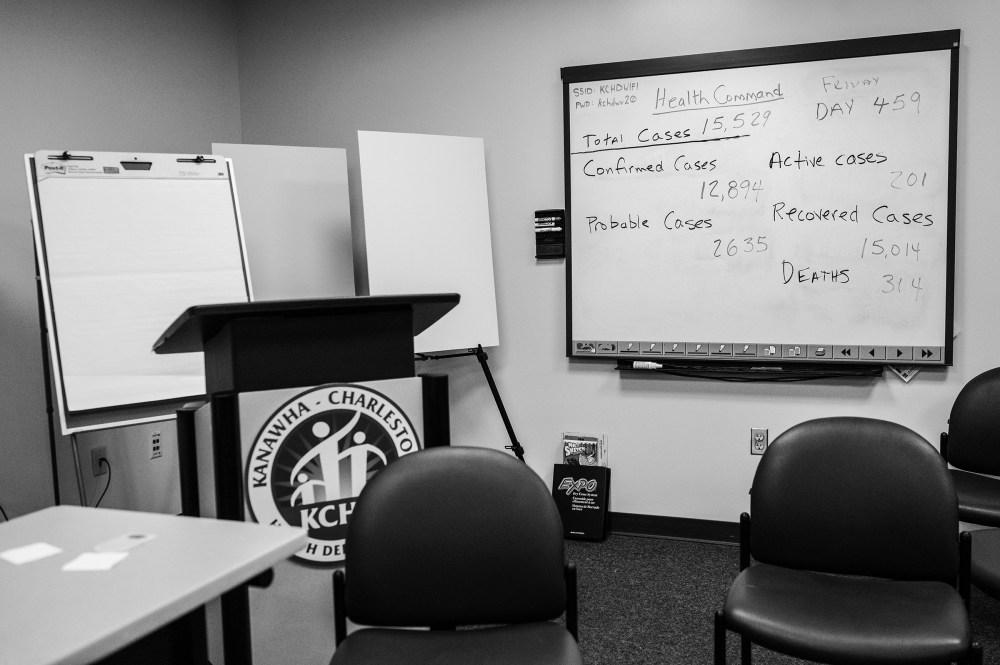

As West Virginia’s most populous county, with about 180,000 residents living across roughly 900 sq. mi., Kanawha has logically reported the state’s highest raw numbers of COVID-19 cases (15,624) and deaths (318), but its case rate is much lower than those in many nearby counties. Since the start of the pandemic, about 8,700 of every 100,000 Kanawha residents caught COVID-19, whereas in tiny Pleasants County (pop. 7,460), that rate stands at more than 12,800. Kanawha County has also been remarkably successful at vaccinating quickly and broadly. As of June 22, almost 47% of Kanawha County residents (and 54% of those 12 or older) had been fully vaccinated. By June 21, only 29% of U.S. counties—more than a dozen of them in West Virginia—had vaccinated at least 40% of their people, according to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data. Just 8% had topped 50%, a threshold not far out of Kanawha County’s grasp.

Young knows her county’s success will surprise many. Pre-pandemic, West Virginia ranked first in health metrics no one would want to brag about: prevalence of poor physical and mental health, cardiovascular disease, obesity. Poverty and addiction are rampant, and access to health care can be limited outside the Charleston urban area. None of that screams “national success story.”

Kanawha is the exception to numerous trends. Rachel Garfield, who tracks county-level COVID-19 data at the Kaiser Family Foundation, says areas with high rates of poverty, uninsured people and residents of color tend to lag behind their neighbors in the U.S. vaccine rollout. Highly educated populations, as well as those that skew Democratic, tend to be more open to vaccination.

While Kanawha County is about 90% white (well above the national rate of 60%), about 16% of its residents fall below the poverty line (compared with a national rate of 10.5%), and about 8% don’t have health insurance (below the national average of 9.2%). Only about a quarter have a college degree, and 56% voted for Donald Trump in 2020. And yet, Kanawha has succeeded where other counties haven’t. “There could be some on-the-ground factors that are hard to measure,” Garfield says. “It could be that this is really a tight-knit community where people have trust in the system or trust in each other.”

Indeed, Kanawha County officials’ collaborative health-delivery model, intimate understanding of their community and willingness to meet people where they are could help rewrite the textbook for public health in the post-pandemic age. If that model is followed, the big business of health care may turn into something smaller, more localized—and hopefully better equipped to keep us all well.

President Joe Biden wanted 70% of U.S. adults to have gotten at least one vaccine dose by the Fourth of July. Sixty-five percent have received one as of June 22, but Biden will be lucky to reach his target. By mid-June, 850,000 people in the U.S. were getting a shot on an average day, down from an April peak of more than 3 million. States including Ohio, New York and Oregon have resorted to six-figure lottery drawings to drum up interest, and many are struggling to use supplies before they expire.

In Kanawha County, Young and her colleagues are trying to get a shot into every willing arm through any means possible. In addition to pop-up clinics, they personally make house calls to people who request a shot, a strategy also used in states like New York and New Jersey. On one Friday afternoon in mid-May, Young gives a grand total of four vaccine doses during house calls. “The thing to take home is not always the numbers,” she says; every person vaccinated is, in her mind, a small victory.

States that have adopted a similar approach have often been successful. Alaska has vaccinated more than half of its residents older than 12, in part because Alaska Native tribes were active in vaccinating their own members. Alaska state health officials have administered shots on airport tarmacs and in grocery stores, transporting them by sled and snowmobile if necessary. New Hampshire, another state that has vaccinated more than half of its residents, made sure every person could access a shot within 10 miles of their home. In California, where about half the population is fully vaccinated, walk-in clinics have popped up in predominantly Latino neighborhoods. In Michigan, which counts 51% of people 12 and older fully protected, mobile vaccine units have brought shots directly to people in need, from farmers to homebound seniors.

One of the problems with early vaccination efforts, says Dr. Alicia Fernandez, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, was that people were expected to track down mass vaccine sites or hospitals offering the shots. That meant many people without trust in or access to the traditional health system were left out. Taking vaccines and other health care into neighborhoods that need it most, she says, is the best way to achieve equitable and effective coverage.

That’s only possible, of course, if you know where people are and what they need—and in that respect, Kanawha County was prepared. In March 2020, when it became clear that no part of the country would escape COVID-19, Young, county manager Jennifer Herrald Oakley and ambulance authority deputy director Monica Mason pulled together a “health command” made up of people from every county department that touched health and safety, from the sheriff’s office and fire department to the local homeland-security division.

At first, the health command focused on identifying those who had contact with people who tested positive for the virus. As soon as testing became widely available, they set about swabbing nursing-home staff and residents and standing up free testing centers all over the county. When vaccines were first authorized in December, the health command used that same community-health approach to begin distributing shots.

All of this has been a team effort. The homeland-security division and other county officials lent logistical know-how, while the sheriff’s office provided security. The ambulance authority helped with contact tracing, and their medics (along with those from the fire department) distributed vaccines and tests. When asked why Kanawha County has fared so well during the pandemic, health command leaders Young, Herrald Oakley and Mason all give the same answer: relationships and collaboration.

Those things won’t go away when the pandemic ends; they’ll just look a bit different. Kanawha County is already offering HIV screening and care in at-risk areas, and Young also envisions delivering routine vaccinations, medical services for the homeless and perhaps addiction care in community settings, partially inspired by the pop-up testing and vaccine clinics that emerged during the pandemic.

Historically, areas with solid community-health programs have good outcomes. Ethiopia implemented one in 2004, training thousands of people to become health workers and sending them out to deliver care. Since the program launched, mortality among kids under 5 has dropped by half and childhood immunization rates have soared. In the U.S., Texas was the first state to formally recognize community-health workers, in 1999, and since then has excelled with programs that use such workers to connect immigrants and people from underserved populations with the wider health care system.

Of course, any program ultimately needs money to work. Federal funding has made it possible for Kanawha County and others to go to great lengths to distribute vaccines during the pandemic. But what happens after that money runs out?

In Kanawha County, as in many parts of the U.S., public-health funding was progressively cut before the pandemic. In 2017, West Virginia slashed a quarter of its budget for local health departments–a loss of about $4 million—and counties have since struggled to make it up. Federally, the CDC’s budget declined by about 10% from fiscal year 2010 to 2019, after accounting for inflation. But on the bright side, 43 states and Washington, D.C., increased or maintained funding for their public-health programs in fiscal year 2020—a step toward a national system that prioritizes community health after years of “chronic underfunding,” according to a May 2021 report from the nonprofit health-policy group Trust for America’s Health.

Kanawha County has shown what’s possible when a small but dedicated group of people come together to deliver community-centered care. But it has taken a toll. On a dry-erase board in the health department, employees track how long the health command has been fighting COVID-19. The tally is now approaching 500 days. Young, Herrald Oakley, Mason and their teams have worked the vast majority of those days, often grabbing only a few hours of sleep between vaccine clinics. One of the department’s epidemiologists got married during lunch—then returned to work.

Young knows this isn’t sustainable, at least not without institutional support. If the pandemic has shown nothing else, it is that the U.S. public-health system needs more money, more people, more resources. Whether elected officials will listen is uncertain, but Young and her colleagues are prepared to visit as many homes, churches and community centers as it takes to get Kanawha County out of the pandemic and on the path to a healthier future.

“We have to go where people are,” Young says. “That is something that needs to be in the history books. If we do this again, this is the way you do it.”

Comments

Post a Comment